What does Prosecution refer to?

According to the Istanbul Convention, prosecution refers to the existence of procedures and legislation ensuring the prosecution of perpetrators: defining criminal offences, risk assessment and protection orders, swift investigations, and appropriate sanctions.

In the context of UniSAFE and research and higher education organisations, prosecution refers specifically to the handling of cases of gender-based violence by the institution, investigative actions, disciplinary procedures and sanctions for perpetrators, as relevant. In some cases, it may also involve judicial proceedings, including court cases, for criminal and civil offences. Risk assessment, aimed at understanding the situation and risks, relates to several Ps (Prevention, Protection, but also Prosecution), and is covered under Protection.

The following elements should be considered, elaborated in greater detail below:

- Implementing clear, accessible and transparent procedures for handling incidents and complaints;

- Establishing reasonable timelines between complaint, investigation and decision/sanction;

- Mainstreaming a victim-centred, trauma-informed and gender-responsive approach to prosecution procedures, and hence providing specific training on such approaches for those involved in the procedures;

- Ensuring effective communication with the victim/survivor, perpetrator and bystanders throughout each step of the process;

- Implementing appropriate investigation measures and standards of burden of proof;

- Establishing distinct disciplinary procedures for both staff and students;

- Defining criteria for the composition of the investigation and disciplinary committees;

- Imposing proportionate, appropriate and equitable sanctions as the result of the investigation and disciplinary process.

How to approach Prosecution?

Sexual and gender-based violence is notoriously difficult to investigate and prosecute. The various legal contexts applicable to research organisations and higher education institutions in Europe and the variety of situations in which offences occur require flexibility, while ensuring fairness in the disciplinary approach and sanctions. Key principles applying are a victim-centred and trauma-informed approach and a recognition of the specificities of gender-based violence.

EU Directive (2012/29/EU) on establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime provides useful guidance, including for research organisations and higher education institutions.

It is essential to provide a protocol that prescribes what will happen if inappropriate behaviour is reported. A protocol lays out, step-by-step, how incidents of gender-based violence are reported, addressed and resolved in the institution. Read more on “Developing a protocol for addressing gender-based violence in research and higher education institutions – UniSAFE Guidelines”.

The following section provides more details on the elements mentioned above, providing good practice standards for prosecution procedures, investigation measures, and internal disciplinary procedures and sanctions.

Good practice standards related to prosecution procedures

- Internal procedures address gender-based violence separately from general disciplinary rules and procedures. Gender-based violence is not to be treated in the same way as, for example, plagiarism;

- The organisation’s prosecution strategy is known to all staff and students;

- Informal and formal disciplinary procedures are clearly set out, including information on the types of disciplinary action or sanctions (such as verbal or written warning, suspension, dismissal, perpetrator treatment/counselling or ongoing supervision);

- Clear information is provided on what can serve as evidence considering different forms of gender-based violence. Ensure a low threshold to start a formal investigation;

- The complainant and the accused have the right to representation by a trade union, friend or lawyer;

- The organisation does not advocate joint meetings with the parties “to clarify the situation”, external mediation or “conciliation” procedures. As laid out in the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and addressing violence against women and domestic violence, mediation is discouraged because victims/survivors of such violence cannot engage in alternative dispute resolution processes on an equal footing with the perpetrator (Explanatory report, article 48);

- Victims/survivors’ requests for confidentiality are respected. If required by law to report a crime, the victims/survivors are informed about it. Reporting to authorities can be linked to assessing a high risk of imminent threat and violence;

- There is no fixed time limit for making a complaint in recognition of the fact that victims/survivors may need time before they are ready to report;

- There are clear and reasonable timeframes for each stage of the complaints and disciplinary procedure.

Good practice standards related to investigation measures

- Investigation is initiated upon a formal complaint or when there are consistent indications of serious suspicions. Consider informal or anonymous reports to evaluate circumstances, context, and conduct of the (alleged) perpetrator to determine the need for further investigation, protective and preventive actions. Read more about formal, informal and anonymous reports here;

- The process for conducting independent internal or external investigations is transparent. If an internal investigation committee exists, its composition is diverse, impartial and representative of the parties involved (e.g. a student is a member if the victim is a student). Including external members in the committee is considered a good practice;

- Investigators are trained on understanding violence against women and gender-based violence (e.g. the role of social norms in perpetuating victim-blaming) and are equipped with knowledge in conducting investigations in a gender-responsive and trauma-informed way (e.g. understanding trauma and its impact on the brain, on memory and the reporting of abuse);

- The burden of proof does not rest solely on the complainant. The mechanisms of shared burden of proof, as provided in EU directives on gender equality, can be considered;

- Investigations and procedures are pursued even if the victim/survivor or alleged perpetrator has left the organisation, recognising the importance of serving justice and institutional learning;

- The findings and recommendations of the investigation committee are fully implemented and acted upon. In cases where implementation is not feasible, clear justifications for the decision are provided;

- The anonymity of victims/survivors and witnesses is maintained to the greatest extent possible when reporting on investigations;

- Investigations and their outcomes are monitored by the organisation (among others in terms of impartiality and fairness). Internal deliberations are conducted on the causes of harmful situations and implement measures to prevent their recurrence.

Good practice standards related to internal disciplinary procedures and sanctions

- Disciplinary committees are composed of trained people representing the different stakeholders (such as hierarchical representatives, students, staff and trade union representatives), while ensuring gender balance;

- The main idea behind disciplinary action is to correct behaviour, which does not necessarily involve sanctions. However, the ability to impose sanctions on perpetrators regardless of their status is essential;

- A progressive disciplinary rationale is in place. This requires that disciplinary interventions are always documented. Depending on the nature and severity of the misconduct, it may be appropriate to use constructive measures and sanctions particularly for milder offences. For instance, individuals who use sexist language may be obliged to undergo specific counselling or training to reflect on and change their inappropriate behaviour;

- Disciplinary sanctions may include a warning, a reprimand, retraining, counselling, ongoing supervision, change of functions, denial of access to promotion or functions, suspension, demotion and dismissal;

Note: Internal disciplinary measures should be independent of the victim/survivor’s decision to report the incident to the police or judicial authorities. If the law obliges the reporting of (impending) crimes by professionals who become aware of such a situation, the victim/survivor must be informed about it.

- Power differentials between the parties are considered when sanctions are decided, applying stronger sanctions for perpetrators whose misbehaviour also constitutes abuse of power;

- Outcomes of procedures are communicated to the victim/survivor;

- Close monitoring of perpetrators is conducted, at least for a certain time, considering measures to prevent the recurrence of misconduct, even if it occurs elsewhere.

Are you interested in learning more about prosecution, investigation, disciplinary procedures and sanctions? Read the Protocol guidelines developed by UniSAFE.

Tips and Hints / Dos and Don'ts

- Initiate an inquiry process based on reasonable doubt, without necessarily requiring a formal complaint, to prevent the escalation of harmful behaviours;

- Explore the establishment of a specific external body to investigate incidents, potentially shared with other similar institutions in the region or country;

- Consider modifying and adapting the duties of the accused person (if staff) or their access to some certain parts of the campus (if a student), such as offering online courses for the duration of the investigation;

- Ensure that a psychologist is involved in the interpretation of facts reported by the victim/survivor and the perpetrator, specifically considering the potential effects of trauma on memory and the brain.

- Make a list of typical arguments an organisation and its leaders may present to oppose investigation or sanctions, and develop counter-arguments. Clearly communicate to the management that fear of potential lawsuits by the perpetrator against the institution (such as defamation claims) is not a valid reason to avoid acting. It should be emphasised that victims/survivors can also sue the institution for inaction or failure to fulfil its duty of care;

- Implement monitoring mechanisms for investigations and sanctions to demonstrate a consistent approach in holding perpetrators accountable, ensuring that “high value” scholars or senior managers are not protected or given special treatment;

- To help prevent a perpetrator re-offending elsewhere, consider recording severe forms of transgressive behaviours such as abuse of power and scientific and ethical misconduct. Penalties for such misconduct may include publishing the outcomes of disciplinary procedures, so that other or future employers can be made aware of them;

- Do not make parties sign a non-disclosure agreement as part of resolving a complaint. Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) can prevent victim/survivors from speaking openly about their experiences and may hinder the disclosure of important information. NDAs can contribute to a culture of secrecy which creates an environment where misconduct can go unnoticed or is even condoned.

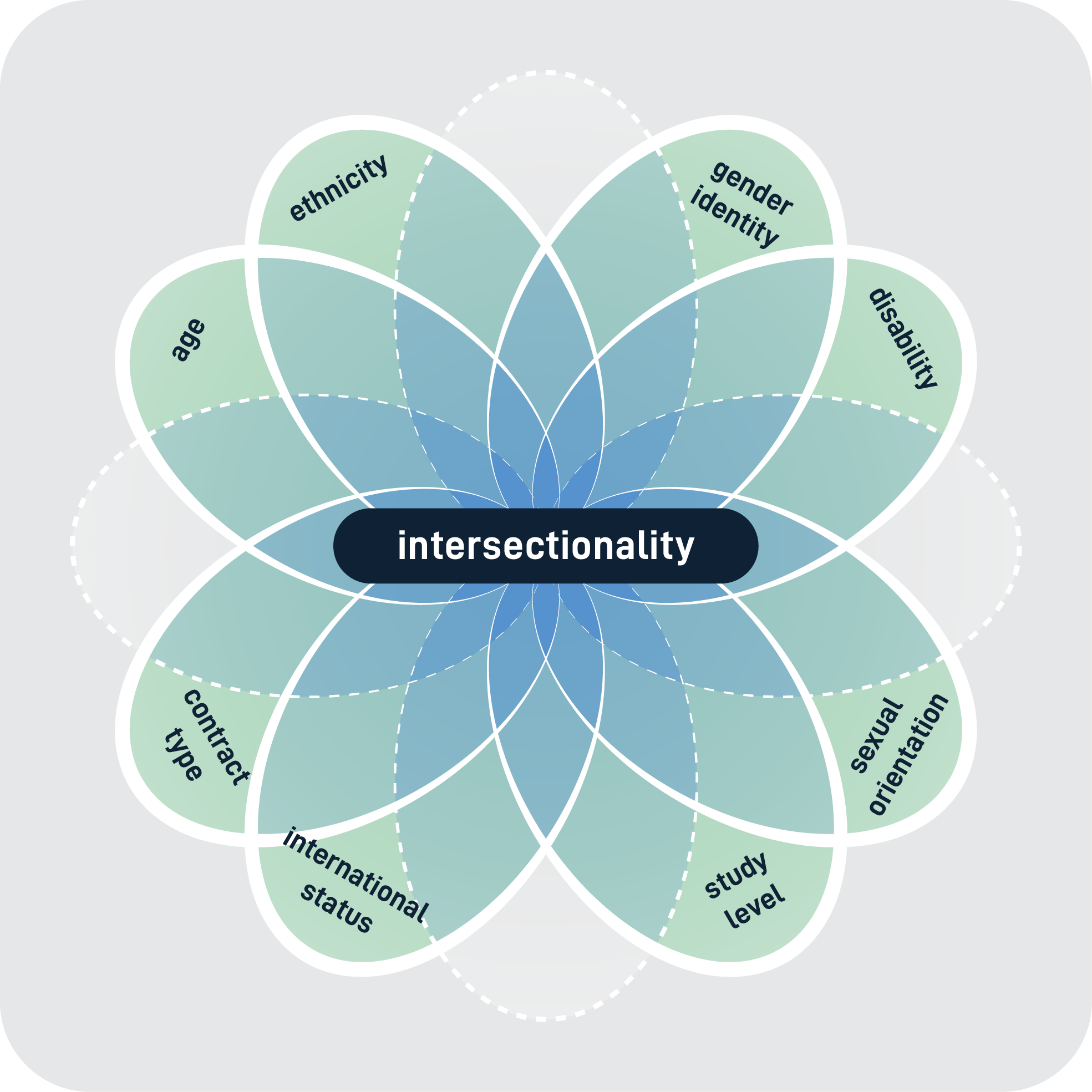

Thinking intersectionally about Prosecution

- All procedures and their respective steps for reporting, investigations and disciplinary actions should account for various types of violence, making reference to institutional anti-discrimination policies and laws (such as on anti-racism, the rights of LGBTQIA+ or disabled people), as relevant;

- Wherever feasible, strive to establish investigation and disciplinary committees that are diverse and include experts who are knowledgeable about intersectional or multiple forms of violence;

- Ensure that all campus law enforcement and public safety officers receive ongoing, up-to-date training on the dynamics of gender-based violence, with a specific focus on understanding the impact of trauma on victims (notably of sexual assault, dating and domestic violence, and stalking);

- Sanctions should consider the presence of multiple and intersectional discrimination when determining their severity (e.g. treating them as aggravating factors).

Inspiring practices

Central European University Policy on Harassment – Central European University, Austria

At the Central European University, the possibility exists to make collective complaints. Procedures allow organisations recognised as being representative of a community, such as the trade union, students’ union or work councils, to bring an informal or formal complaint on behalf of a group of individuals whose allegations relate to the same set of factual circumstances or the same respondent. This may only be done with the express prior consent of those individuals being represented. The specific format for such representations shall be elaborated by way of a separate policy, developed by the Ombudspeople Network and Disciplinary Committee in consultation with the Gender Equality Officer, Trade Union, Students’ Union and other relevant CEU representative bodies.

Abuse of power as scientific misconduct – Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Germany

In the DFG Code of Conduct, which came into force in Germany in 2019, abuse of power is also considered to be scientific misconduct. The DFG´s Code of Conduct “Safeguarding Good Research Practice” reflects the fundamental principles and standards of good practice upheld by the member organisations of the DFG. “These guidelines underline the importance of integrity in the everyday practice of research and provide researchers with a reliable reference with which to embed good research practice as an established and binding aspect of their work.”

The Code of Conduct of the University of Siena, Italy

This is a code of conduct against sexual harassment in the workplace and work environment defining the type of behaviours addressed, providing information on trusted persons within the university and the process of dealing with informal and formal complaints. It has been translated into English by the Yellow Window team using the automated translation tool DeepL.

Disciplinary Procedure – University of Cape Town, South Africa

The University of Cape Town has a separate procedure for sexual misconduct and sexual harassment. The objectives of the policy and this procedural guideline are to ensure that the university disciplinary process for such cases maintains an administrative procedure, based on the balance of probabilities, rather than a criminal process. This standard of proof informs the process and procedure. Proof beyond reasonable doubt does not mean proof beyond the shadow of a doubt.

Disciplinary Actions, Suspension, and Termination of Employment – Durnham Technical Community College, United States

Durnham Technical Community College provides guidance and a framework on disciplinary actions, suspension and termination of employment. The policy aims to ensure a fair and consistent approach with progressive steps to address concerns related to the violation of institutional policies, and lays out the steps to be taken.

Resources and further reading

Developing a protocol for addressing gender-based violence in research and higher education institutions – UniSAFE Guidelines

The guideline document developed by UniSAFE gives guidance to research and higher education institutions in designing a protocol to address gender-based violence. The guidelines explain what a protocol is and which elements it should cover, along with practical tips and sample practices. The primary audience for this guide includes staff members responsible for developing and implementing a protocol within their institutions. By following these guidelines, institutions can create safer environments and establish effective measures to address gender-based violence. Explore further.

Disciplinary Action at Work: All HR Needs to Know – Academy to Innovate HR

This article highlights the significance of disciplinary action in the workplace. It provides general advice to human resources managers on disciplinary sanctions to create a safe and productive work environment, providing insights into various behaviours that may warrant disciplinary action. It offers examples in a scale of sanctions from verbal warning to termination. It also outlines best practices for HR professionals in handling disciplinary actions effectively. Explore further.

Sector Guidance to Address Staff Sexual Misconduct in UK Higher Education – The 1752 Group and McAllister Olivarius

The 1752 Group and McAllister Olivarius have published the “Sector Guidance to Address Staff Sexual Misconduct in UK Higher Education” addressed to higher education institutions. It offers a thorough set of recommendations aimed at effectively handling student complaints regarding staff sexual misconduct. The guidance outlines critical suggestions for each stage of the end-to-end procedural process, ensuring a more structured and sensitive approach to addressing these serious issues within the academic environment. Explore further and download here.

Effects of trauma – Jim Hopper

Jim Hopper writes on how stress and trauma can alter thinking, behaviour and memory formation after sexual assault – which has important implications for justice, healing, and prevention. Short video explaining impact of trauma on the brain and recollection of facts of sexual assault. Explore further.

EU Directive (2012/29/EU)

EU Directive (2012/29/EU) on establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime provides useful guidance for research organisations. For example, the directive, which should have been implemented in all Member States, provides for:

- The right to be given detailed information about the criminal justice system

- The right to be given information on victim support services

- The right to be kept informed of the progress of the investigation and any court proceedings

- The right to have protection needs assessed and have measures put in place to stop further victimisation and intimidation

- The right to be told of a decision not to prosecute and the right to ask for a review of that decision

- The right to be given information in clear language and to have access to interpretation and translation services, if needed

Code of Practice for Employers and Employees on the Prevention and Resolution of Bullying at Work, Ireland

The Health and Safety Authority and the Workplace Relations Commission prepared this code of practice jointly. Its purpose is to provide guidance for employers, employees and their representatives on good practice and procedures for identifying, preventing, addressing and resolving issues around workplace bullying. Explore further.

The contents of this website were developed by Yellow Window and do not necessarily reflect the views of the EC. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 101006261

The contents of this website were developed by Yellow Window and do not necessarily reflect the views of the EC. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 101006261